“Until the lion learns how to write every story will glorify the hunter.” Time and again, history has borne witness to the truth of the above proverb. Africa, the place of its origin, during its colonization, was, (and perhaps is, even now, in certain senses) a stark embodiment of the proverb—its people violently enslaved, and their voices subdued and erased from a world that admired the ambition and bravery of their colonizers.

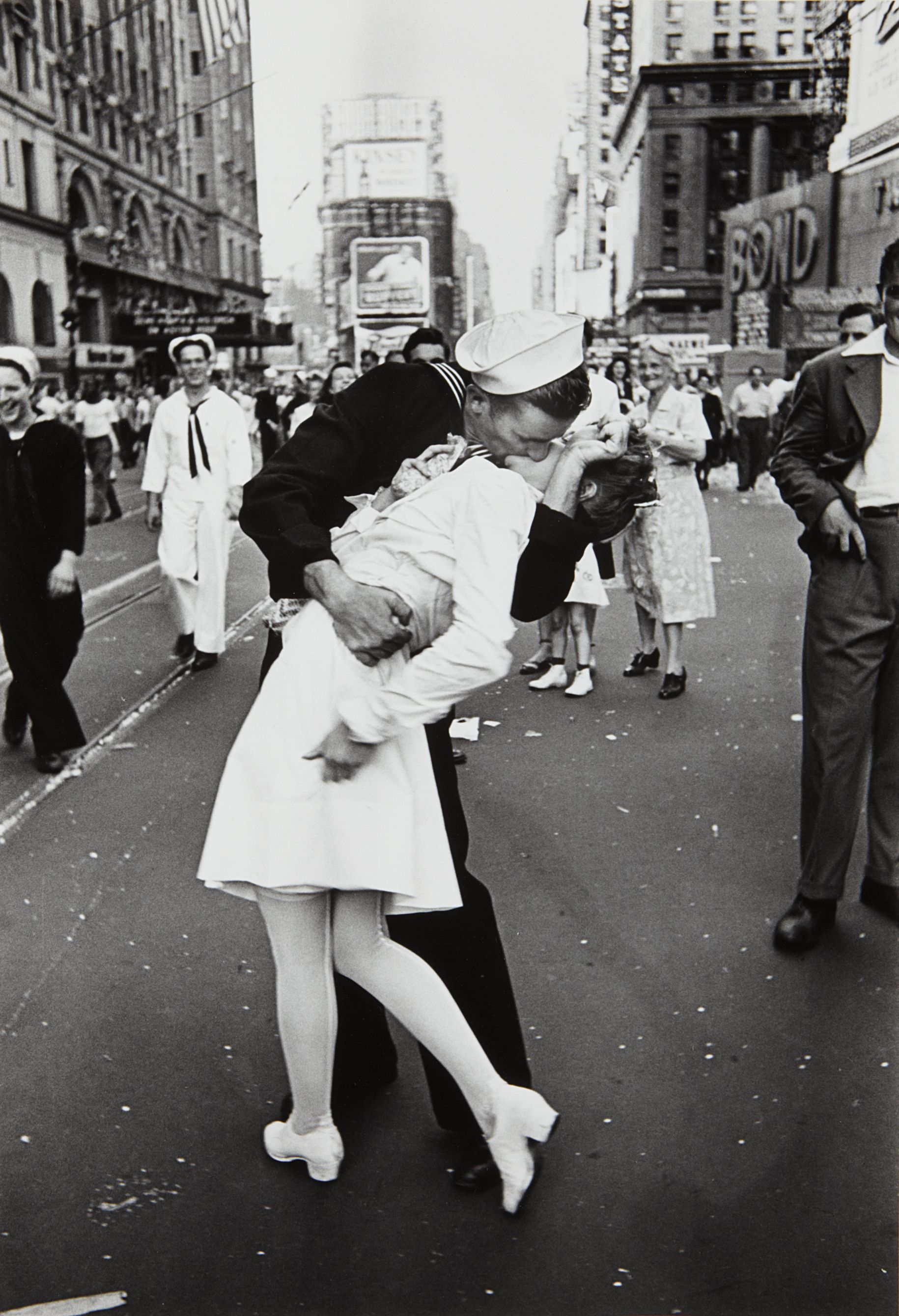

Consider the famous “V-J Day in Times Square” photograph captured by Alfred Eisenstaedt in Times Square, New York City, on August 14, 1945, the day Japan surrendered, and thereby effected the end of, World War II [1].

The end of the war was being celebrated with great joy and zeal in Times Square, when an ecstatic and drunk U.S. Navy sailor grabbed a female stranger, bent her backwards, and kissed her while holding her head in place with his arm. A week later, a photograph of this incident was published in the LIFE magazine and was later hugely acclaimed as a depiction of unrestricted joy, and as one that represented the glorious victory of the nation and the sentiment of the entire people. The photographer was hailed for his momentous capture of a passionate moment symbolizing the magnificence of human emotion at a time so perfect. The picture became an icon of freedom, romance, and skilful artistic timing. While almost every description of the photo contains an admiration and romanticization of the spirit of celebration in the soldier and of its capture by the photographer, barely much is said of the agency or standpoint of the woman who was kissed against her will (as is clear from description of the photographer in his book, from her own words after she was identified as Greta Zimmer Friedman, and also by the account of the sailor). Until recently, it was never acknowledged or publicly even conjectured that what the picture truly did depict was nothing short of sexual assault. While the event’s descriptions were fairly vivid and pointed evidently to the act being forced upon the woman, its being an act of assault was pushed (perhaps subconsciously) under the rug of the common solidarity of “celebration”, and “unconstrained joy” it elicited as a new cultural icon.

In Jane Austen’s novel, ‘Persuasion’, Captain Harville comments, “I do not think I ever opened a book in my life which had not something to say upon woman’s inconstancy. Songs and proverbs, all talk of woman’s fickleness. But perhaps you will say, these were all written by men [2]." To this, Anne says, as part of her reply, that “men have had every advantage of us in telling their own story. Education has been theirs in so much higher a degree; the pen has been in their hands. I will not allow books to prove anything. [2]"

Indeed, the depiction of women throughout a large part of history, be it literary, philosophical, religious, or scientific, has been of a distant, inferior, “other”, less rational, excessively emotional, and suited to inhabit the domestic sphere and needing to be controlled by men. The “V-J Day in Times Square” photograph and its receptions are iconic indeed, not of romance, but as examples of how history and culture, among other things, are shaped when pens and cameras lie disproportionately in the hands of a particular social group.

In her book, “The Man-Made World, or, Our Androcentric Culture” [3], Charlotte Perkins Gilman introduces the concept of androcentrism, a rendering of a masculine point of view as central, universal, default, or objective, in one’s worldview [4]. She argues that family, culture, history, economics, religion, society, etc. function from an androcentric view, under which the human becomes synonymous with the male, whereas female becomes the other sex, a deviant from the male, whose several qualities are inferior exceptions to the natural human (male) nature. Further, Gilman describes the hegemony of patriarchy and male dominance that have pushed women into the domestic sphere, engaging them in only what is considered the “feminine” occupations and activities, and denying them what she considers is a natural human need to work (in an economic sense). Androcentric divisions, for her, were abnormal restrictions that needed to be done away with for women to realize their natural instincts.

What implication, then, does androcentrism have on sociology, the study of society, of which humans form the core? Does the ‘human’ component of sociology truly represent humanity or does it assume the term ‘human’ to be interchangeable with ‘man’? Since women, in the past, were pushed away from the public domain and their lives were restricted to the home and family, and since sociology was essentially focussed on a study of the public and the social, rather than the domestic, it is plausible that sociological study was of the male world, and neglected the lives of women altogether.

One may now go back to the “V-J Day in Times Square” in all its glory and ask how much of the fame it acquired could be credited to the centrality of the male eye viewing it and the male mind interpreting it. It is no longer surprising that a photograph of an overjoyed, virile Navy sailor celebrating his country’s victory and exercising his right to do so at a cost to another person, especially a non-male, can be related to almost exclusively by the male mind. The notions of ‘country’ and ‘freedom’, here, are interchangeable with men of the country, subsuming the interests and experience of the “other”, the woman. This absorption of the stances and interests of non-dominant groups into those of the dominant, is in no way restricted to mere public and cultural icons or the media; it finds its way into every sphere of human life: culture, religion, politics, and academic disciplines such as the natural and social sciences (among most others).

The Canadian sociologist and feminist, Dorothy Smith, elaborates on how the conceptual rules, methods, procedures, theories, and structure of the traditional sociology are inherently patriarchal and based upon the male social world, and thus marginalize women and their experiences [5]. She notes that the woman’s social world is subordinated to and dependent on the man’s and consequently, women (in particular, women in sociology) are forced to think in terms of male-defined and male-centric concepts. In close relation to institutions of societal control, which are always external to the people participating in them, is the depersonalized sociology that subsumes people’s personhood and experiences and discards their reliability as information sources about the social world, via its ethic named objectivity. Smith argues that it is impossible for an observer to erase their spatial and temporal location in society, as well as their own experiences, while doing research. Further, for a sociologist to work in an abstract and “objective” framework, they must be separated or alienated from their own local existences. Thus, the sociologist is objectified and separated from their own knowledge, and this knowledge loses its applicability to real societies and people.

Smith uses women’s neglected perspective as evidence of the failure of sociology’s claim to objectivity, establishing that what is legitimized as true and genuine knowledge is often tainted with the bias of a dominant, powerful category. This finding, she says, must lead to a reorganization of its core methods and the relations within the field. Differences in locations and experiences are to be exploited for knowledge production rather than concealed. An observer may understand a particular sociological world much better from within as that person may then relate to the real-life experiences of the subjects. Consequently, the knowledge produced under this framework would serve the interests of the society being study by producing an honest and empathetic depiction of them to the rest of the world.

Patricia Hill Collins, a feminist scholar and standpoint theorist, made yet another crucial contribution to the argument for studying a sociology from within [6]. The feminism she saw around her was a “white feminism” and made her recognize that the experiences that were considered to be ‘of a woman’ were actually of a white woman, and did not entail the distinct history, society, culture, lives, or experiences of black women. She identified that the ways in which black women were oppressed and stereotyped were very different from white women, and how the slave system (and later, racism) rendered their realities, and the division between the black male and the black female worlds, as well as between the white female and the black female, very separate. Thus, while white women were subdued and marginalized because of their gender (and possibly economic status), black women had the added burden of race violently oppressing them, as well.

One sees, thus, with the introduction of an insider perspective and an emphasis on experience, the important role played by emotion in sociological research. Experience, in most cases, among other things, constitutes emotions as an important part. Emotions are an integral part of human life, and by extension, an integral governing factor of society, and thereby elicit an appropriate representation in sociological research. Indeed, some of the core sociological categories studied: family, religion, relationships, self-identification, etc., are based largely upon the dynamics of human emotions, a dry and purely empirical and rational documentation of social phenomena does not suffice. One of the most pressing issues of today: that of religious fundamentalism, of the freedom of belief, the right to the gender one identifies with, the freedom to love and marry transcending one’s sex and gender, child rearing, racial and gendered hatred, economic alienation, etc., all encompass emotion as a fundamental component. Neglecting emotions while studying sociology and subsequently in policy-making, is not only irresponsible, but may be lethal to the stability of the society. Emotion in sociology must be taken into account, understood and analysed, and further presented, in a fair and unbiased way, giving weight to the experiences of the members of the society itself rather than abstract conceptual principles.

The wide applicability and importance of studying sociological ideas from within a context rather than from outside cannot be overstated. One of the most radical an influential theories, that of Marx (who was a major influence for Dorothy Smith): his critique of capitalism and his and his idea of a communist society, was one that came not from an outsider or ‘objective’ perspective, but from one that delved into the lives, minds, and emotions of the wage labourers of 19th century Europe: their poor working conditions, their struggles, the production of their psychological state of alienation, the need for a ‘class consciousness’, etc [7]. Marx’s goal was never to merely study or classify social entities, but to bring about change for the working class by bringing their condition to their own and to others’ light, and by stating in clear terms what he believed would bring about a better and equal world for humanity. In no way did Marx’s own empathy for the working class deter the validity and applicability of his theory; rather, one may argue that his passion actually enhanced the ideas and knowledge he produced.

Another domain where the importance of an insider’s view becomes clear is that of area studies: the representation of the government, cultures, societies, and history of a particular place, say a country. One may take the example of the sociological knowledge produced during the colonial period in India, which one may now refer to as part of the Orientalist discourse [8, 9]. The knowledge and theories on Indian society were in almost unanimously biased by the European backgrounds and histories of the observers: the concepts, methods, standards and measures were Eurocentric under the pretext of scientific objectivity, and the ideal for comparison with was European society. Indian input was largely missing or suppressed. The dangers of such a structure are emphasized here once again, for this knowledge was used as a tool and justification for the violent domination of the Indians.

Another similar example is the current representation of the Middle Eastern countries in the Western mind: that of a despotic, lawless land with barbaric people governed by a primitive religion. Several judgements and stereotypes by Westerners (even academics) are undoubtedly unfair, especially considering that their own religion and society are far from perfect, and it is found that insider perspectives from academics, journalists, and activists from within the Middle Eastern societies are far more accurate and useful in improving their society [10]. Muslim women constitute group that face multilayered oppression, and struggle for representation in their own local setting, as well as the international (which has largely become synonymous with Western) opinion of them as voiceless, submissive, and needing rescuing, with Western feminists deciding for them their interests and needs. In India, too, the Muslim woman’s opinions for her own religion and gender are subsumed by the opinions of Muslim men, and of non-Muslim women and men.

Clearly, this politics of representation pervades sociological studies, political action, as well as common mindsets and depictions. Intersectional feminist theory, which looks into the positioning, interests, experiences, and emotions of a social group, is widely applied these days to understand and represent the positions of a wide variety of identities: the cisgender women, transgender women and men and their positions, women and men (and intersex people) of colour, various religions, cultures, and ethnicities, and so on.

The emerging field of Critical Animal Studies questions the anthropocentrism of sociology and other domains of study, and argues for species being an arbitrary distinction to limit one’s perspective (as was argued for sex, in opposing androcentrism) and that non-anthropocentric, empirical evidence for cognition and emotion in non human animals must be considered in determining the social ethics governing their treatment. Once again, it is made clear how a constant outsider representation of non humans has led to their subjugation and instrumental use by their human dominators. In his book ‘Science and Ethics’, Bernard Rollin [11], a philosopher and biomedical scientist, argues that the majority of scientific experiments conducted to gauge the nature of animals’ thought process and emotions, have been by default biased towards humans, assuming them from beforehand as the standard for comparison, and also not free from the prospective material gains in using the animals for human benefit. Such scientific knowledge has for long informed the social sciences, which have been devoid of non human representation.

Thus, what began as a recognition of the absence of women’s experiences has now grown into a need for the recognition and representation of all experiences in sociological study and social policy-making. The initial white feminism is becoming more and more intersectional, and feminist theory is becoming less about only (white/cis/straight) women and more about all groups striving for representation and equal rights, transcending barriers of race, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, religion, and, recently, even species.

References

[1] http://100photos.time.com/photos/kiss-v-j-day-times-square-alfred-eisenstaedt

[2] Jane Austen, Persuasion, John Murray (1817)

[3] http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/777290.The_Man_Made_World

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Androcentrism

[5] Dorothy E. Smith, Women’s Perspective as a Radical Critique of Sociology

(1990), University of British Columbia

[6] Black Feminist Thought in the Matrix of Domination:

http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/252.html

[7] Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Communist Manifesto (February 1848), United Kingdom

(Original language: German)

[8] Edward Said, Orientalism, Pantheon Books (1978)

[9] Imagining India: An Intellectual History of Orientalism, Course taught by Dr. V. Rajesh,

January–May 2017, BS-MS programme, IISER Mohali

[10] Women’s rights in Afghanistan:

http://www.refinery29.uk/womens-rights-afghanistan

Being an ally to Muslim women: https://www.bustle.com/p/how-to-be-ally-to-muslim-women-truly-embrace-intersectional-feminism-49412?utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=owned&utm_campaign=feminismbustle

[11] Bernard E. Rollin, Science and Ethics, Cambridge University Press (March 27, 2006)

[12] Michele Dillon, Introduction to Sociological Theory : Theorists, Concepts, and Their Applicability, 2nd ed., Wiley Blackwell

[13] Nivedita Menon, Seeing Like a Feminist, Penguin India (2012)